Abundance and Morality

Most people like to think that they are fundamentally moral beings. That they would sacrifice for others, even risking their lives to save a stranger in distress. There are people like that.

But would you give away a loaf of bread if your children are already going hungry for days? Would you take a loaf of bread from a hungry person to feed your starving children?

The Bad Old Days

Almost regardless of your answer, it is definitely true that a significant portion of society would indeed use violence to secure food for their starving family, even at the expense of their neighbors. A major part of human existence 5,000 years ago was raiding. In many places and at many times there was not enough food. Even after the Agricultural Revolution occurred, human groups were almost always one bad harvest or one locust swarm away from starvation.

It was very normal everywhere for violent raids to occur because of this food insecurity. Almost everyone today would see a violent raid, with fire and murder and stealing as a very immoral set of actions. And of course they are very immoral. But if the choice is watching your children starve…or violence, a lot of people will pick up spears and torches. This raiding actually was bred into the men fairly consistently, as being a “good provider” in a dramatic way actually increased what anthropologists call “bridewealth.”

The Just Slightly Better Old Days

The response to this was walled cities of a few thousand people, surrounded by a good farmland. This cooperative behavior created food security via physical security. But it also created a basis for higher morality. Helping your neighbor out with food became a strategy that helped you, because that neighbor needed to be able to help build and guard walls, and you need those walls. Specialization also began, and one can imagine that a person might have eschewed farming altogether in exchange for being paid in grain to do nothing but wall-building.

Embedded deeply within this corporate understandings of a common good is a deep empathy. This sense has been rediscovered by anthropological researchers, too and re-labelled as “urban empathy” in the last decade. Such corporate town empathy might not have been present between non-family members of separate but neighboring tribes. One could argue that in the walled city situation, social morality was easier because it made more sense.

And so, arguably city dwellers acted in ways that we would observe today as more moral.

National Moral Fiber

And because a hallmark of humanity is noticing when good things work and then maximizing that function, cities grew and merged into confederations of city states and eventually proto-nations.

Specialization increased, and thus cross-societal empathy increased. People saw the need for other people, and so more people supported each other, even without familial bonds. Violence between strangers within larger and larger groups shrank on a per capita basis.

Unfortunately, this specialization also enabled trans-national raiding on an immense scale. Today, we call this invasion and war. Beginning about 5,000 years ago in Egypt and Nubia, extended raiding campaigns that stretched further than previously imaginable in time and space began to exist, with armies devastating entire regions.

Now, those giant invasions didn’t happen all the time. One could even say they were rare compared to the every-other-month raids of tribal hunter-gatherer life. Large invasions from any single country likely only occurred once every decade or two on average. This is because the larger national organization didn’t usually have annual scarceness of food to deal with. Back 4,000 years ago, disease and general infant mortality kept population growth quite slow, and so the total calories needed by a society one decade weren’t drastically different than the total caloric needs a decade hence.

But still, droughts and blights and locusts did occur once in a while, and many times the only way to keep your people from starving was to go steal food en masse from the neighbors. And even if that didn’t work out very well, at least you would come back with fewer mouths to feed.

National Subjugation

The next forward step in morality came from the realization that if you killed most of the people in the region your nation invaded, then those people weren’t able to make more stuff for you to raid (being dead). So around 3,500 years ago, it became more normal for countries to subjugate other peoples as vassal states.

This was a better deal for the conquered peoples, because they weren’t dead. It wasn’t great, because the stealing was more prolonged and systematic, and the vassal states could often only survive and thrive by groveling. There are 350 cuneiform tablets called the Armana letters that record the obsequious groveling of the rulers of vassal states to their Egyptian rulers. Note that “a step forward in morality” isn’t exactly a glowing endorsement. Better doesn’t mean good. But it did increase trade and security somewhat, and it was way better than if Egypt had just killed most of the people they raided.

Feudalism

One could argue Feudalism was a step backwards, in that it was very much like almost everyone inside your country became subjugated. But the feudal peasants did enjoy some security, both physical and economic, by being under a Lord’s control. This also maximized land use pretty well, in that invasions of one feudal area by another were made a little less common than if the patchwork of farms had all been independent.

Today, it’s obvious that feudalism is far worse than an open market of farmers all competing, but the security and abundance of capital and banking were not typically available in the Middle Ages of Europe in a way that would enable wealth liquidity necessary for expansive economic progress. And the Lord’s security was an important stabilizing guarantee. More abundance ensued, very slowly, under Feudalism, even though being a feudal peasant was not a very pleasant life.

A Counterpoint From A Huge Step Backwards

Chattel Slavery was a huge step backwards, morality wise. The gross and horrid “automation” of bought human labor did increase wealth for a few at better profit rates than the margins gained by those that, you know, actually paid for labor. The industrialization of kidnap, transport, and sale of human beings became quite horrifically efficient, and brought economic “development” to areas that used it. But at the cost of men’s souls.

I find it an interesting point that the technological progress of the cotton gin and other forms of automation made it easier for governments and states that had become dependent on slavery to ban it, because the machines did the “slaving” to some small extent. But the progress that allowed slavery to end was moral much more than technological. The work of the Abolitionists and others, along with the political upheaval that resulted in the American Civil War are what ended slavery.

This episode in history is an important counter-point to the thesis of this essay, in that the economic abundances brought by slavery (to a certain class) did not result in the abolition of the horror of slavery. In fact, there are still on the order of 30 MILLION people in de facto slavery today, and that number is increasing even over the last five years. Giving to charities such as International Justice Mission that literally help free individuals from slavery is a way to do something about this.

The Better Days Today

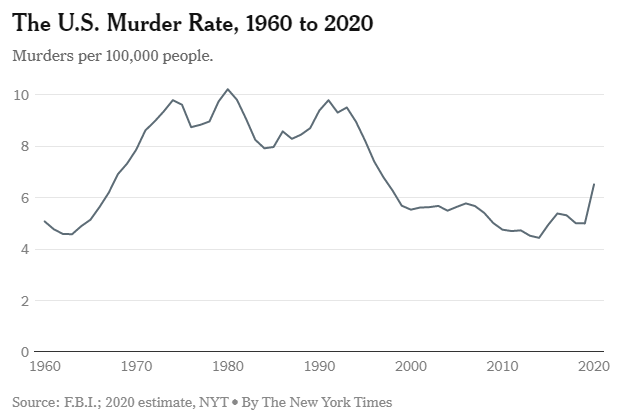

In the West, we live in relative abundance now. But there are still pockets of extreme violence in many countries, especially in some parts of cities. Extreme violence (assaults, rapes, and murders) are huge moral negatives. While on an average per-capita basis, we live in one of the most peaceful time ever, that is not true for all of us.

But in places where poverty is high, those per capita rates are twice as high as for middle income Americans:

The data seems to indicate that at a personal, neighborhood level, abundance helps stave off violent crime. Not some sort of super-abundance, but rather having enough so that you are not a desperate person.

All the things we talked about in terms of tribes and city-states and nations applies to families and neighborhoods as well. The number one way to reduce violence is to decrease economic desperation.

There may be many ways to do this, but we must be very careful in how we do it. We have seen the debilitating effects of certain types of welfare that create perverse sociological incentives. Even providing government-subsidized housing (which seems wonderful on the surface) often leads to economically depressed, violent ghettos and de facto segregation, which are societal cancers. We have to be very smart in providing the right type (and timeframe) of charitable help and even more importantly opportunities to help alleviate this. How is really beyond the scope of this article. But much is at stake here; and careful, non-political thought on this important subject is encouraged.

Three Days or Three Months from Violence?

The scariest related realization of this strong connection between abundance and morality is that all civilized society is only three months of food supply disruption from mass anarchy, which would result in an absolutely massive spike in violence.

There is a very high correlation between high food prices, food shortages, and civil unrest. Food security should be the number one priority of any government.

The government of Sri Lanka was recently overthrown because there were food shortages. Why were there food shortages? There were very bad financial mistakes by the government that resulted in international financial difficulties, and this made importing food more difficult. But also Sri Lanka adopted nitrogen bans urged by the European Union. This resulted in a collapse of local farming output, because nitrogen is the most important component of fertilizers. Sri Lanka valued other things higher than food security, and its capital was swarmed by hungry people.

Several European countries are beginning to restrict nitrogen right now, most notably the Netherlands. Farmers are protesting now, but the Netherlands is one of the breadbaskets of Europe. The wider Dutch public and neighboring Europeans may be rioting soon if this results in food shortages (especially because Ukrainian wheat exports may also be threatened because of the war).

Violence may drastically increase because governments are sabotaging food abundance.

Further, we see some governments sabotaging energy abundance by accelerating the cancellation of nuclear plants and fossil fuel plants as parts of accelerated Green agendas. This article only urges caution.

Three months without food can cause anarchy for a government. But just 2 days without power can do the same, because many peoples’ water supply depends on electrical delivery via pumps. Thirst becomes a problem in a day and half. People will not wait to riot. Water is the most basic human need, and so the electricity to provide water is the most basic human need. Governments should take every measure to keep their electrical power as cheap and stable as possible, or they risk creating water shortages. This ends societies.

The Future of Morality

As humans find more and more ways, mostly through technological progress, to create more and more abundance, we will have the luxury of gaining “higher” levels of morality. I only put that in quotes because I live now. Our grandchildren will absolutely be aghast at the moral cesspool of the early 21st century. And they will be able to ride that high horse of increased morality because of societal abundances.

“How could you make people spend so much time driving when there were 40,000 traffic deaths every single year! Didn’t you care more about lives than making money?!?”

Our descendants will be able to say this because of abundant work from home career options and self-driving cars.

“How can you justify raising chickens and cows just to kill them for food? They are sentient creatures worthy of an independent life!”

Our descendants will have many tasty and diverse protein options, such as lab-grown meat, that will allow them easy moral choices.

“How can you just keep birds — the animals that fly in the sky — as pets in a cage all the time?”

This one isn’t out of abundance. It just makes sense. Keeping birds in cages as pets is immoral and one day people will wake up to this.

Our grandchildren will probably also find abortion to be quite immoral for two reasons. First, hopefully there will be such abundance that any argument that life is hard will be muted. Second, underpopulation issues will be front and center by the mid and late 21st century, and every new human will be valued and desired. Yes, I know…abortion is a hot-button issue. You can take or leave this morality prediction as you see fit, but I am fairly certain it will come true, largely because we will have an abundance of resources and a dearth of humans.

Rightly or wrongly, our grandchildren will judge our current moral status from within their own abundance framework. I truly hope they will live more abundant lives than we do, just as we live much more abundant lives than our grandparents. And while not all aspects of morality are tied to abundance, higher levels of goodness are often seen with more widespread abundance.

We should do all we can to hand our children the most moral future possible. A big part of that is teaching them emotional, spiritual, and psychological maturity. But an important part is also giving them freedom from need.