Automation and More Employment

“Automation is poised to take over 57% of human jobs.”

So many people have been warning about the “impending cliff of permanently high unemployment about to be caused by automation” that the average person has actually started to internalize this as a basic truth. I have had many, many conversation about what to do when — not if — the unemployment rate goes permanently to 20%+ as Artificial Intelligence and robots take over the labor market. And I have been listening to this for well over a decade.

A decade, by the way, that has seen more insane amounts of automation than anyone could have imagined. Let’s recap: since 2012,

Drones can fly themselves automatically to stay near us, do waypoint navigation, and hover faithfully in very strong winds.

AI can automatically find any type of thing in pictures

AI can automatically find any type of thing in video

AI can automatically create almost perfect pictures and videos of people and things by itself.

Self-driving cars are now safer on highways than human drivers

Tweets and Facebook posts are now auto-translated to and from all major languages

AI now writes a significant number of marketing blogs, emails, and websites.

Robots now deliver lunches all by themselves from blocks away.

And these are only a few highlights. Note that none of them have resulted in more unemployment in any industry. There is now more demand for drone operators, truck drivers, image analysts, video game designers, video creators, marketers, and Uber Eats drivers than ever before. This was true before, during, and as we come out of COVID-19.

It’s difficult to see any part of the economy that hasn’t seen massive integration of Automation and smart tools. Wal-marts have automated registers, walk-out-the-door payment systems, and floor-cleaning robots. Amazon warehouse workers toil side-by-side with robots. Paralegals, radiologists, truck drivers, and financial news writers all have had major portions of their jobs strongly impacted by AI, whether it’s Google Maps warning of speed traps or short financial articles written by computers.

In the last decade, more automation has occurred than in all decades that came before, and it lurched deeply into white collar work for the first time.

But here is what the unemployment rate has done in the last 10 years prior to Covid:

Remember, during this time of recovery from the Great Recession, automation drastically increased each and every year.

An even more convincing argument that automation has not drastically changed the need for labor is in looking at something called the Total-Factor Productivity.

When economists look at the entire output of an economy (Y in the equation above), they take the total capital investment (K) and the total labor done (L), and then they multiply these by the Total-Factor Productivity (A). Usually they know Y and K and L from surveys.

As you can imagine, when steam powered machines were introduced into society, that Productivity (A) went up, because more useful work could be done using steam power than without. Same for the introduction of electric motors and computers. In the graph below, you can sort of see the electric motors becoming more widespread in the 1950s and 1960s, and you can see the computers coming in the early 1980s through the present. In both cases, the productivity graph increases its growth rate, making the upward slope steeper.

But even though AI and other new types of automation have come in and made their way into many industries in the last decade, we don’t (yet?) see a dramatic slope up. Meaning that automation is not yet changing the fundamental productivity of the economy very much.

But even more important in this graph is the fact that even when we did see big productivity gains, this didn’t mean that unemployment went up and stayed up.

The Automation-Unemployment Chicken Little crowd claims that automation and AI will allow productivity to go up very significantly without an increase in Labor, completely decoupling economic growth from the need for humans working. We see zero evidence of this now (in the near record low unemployment rates, or in the steady productivity factor), and we didn’t see it when other major technologies did increase productivity significantly.

So why do we have this unintuitive situation, wherein more automation in almost all industries has resulted in lower unemployment rates in almost all industries? Well, first of all, I am not sure that automation caused low unemployment. I am sure that it did not cause high unemployment, because automation went wild while unemployment went to 50 year lows. But even so, why did automation NOT cause a lot of job losses?

The reason for this is that automation almost always empowers workers and rarely replaces them. Once can always find a few examples of worker replacement. But businesses usually realize that:

If the simpler tasks are handed off to automation, employees are freed up to do higher value-add tasks. Using robots to mop the floors frees up employees create more attractive product displays. Drones taking pictures of construction sites by themselves lets survey workers create more useful and deep analytics of the construction site pictures. Automated infrared cameras with image analytics at power plants empower plant operators to spend more time optimizing the plant and less time inspecting the plant.

Automation and AI add to the toolbelts of workers, giving them superpowers. AI taught UPS drivers to always turn right, saving huge amounts of gas and time. The same could be said for Google Maps1. It’s already revolutionized quantitative stock trading, patent research, case law research, and is starting to make significant headway into the interpretation of medical imaging and medical data interpretation. Your pharmacy may have utilized AI to help keep you safe from rare drug interactions and the short sports article you breezed through this morning might have been written by an AI. But none of those industries have an employee glut. Why? Because AI and automation give the existing employees superpowers and brings new employees up to high skill level more quickly.

I have been working to add AI to heavy industrial settings for almost a decade now. I have never added a functionality that has been used or intended to end a job. In every single case the company sees the automated drone or image recognition or smart data stream as something that enables faster work for their employees, allowing them to do their job more completely and more quickly. And the dollar-signs in the employers’ eyes is not based on reducing headcount. It is in making each employee more valuable and more precious. These employers want to enable their employees to contribute more to the bottom line. And they can do this by enabling them with these new tools.

I am not saying zero jobs will be eliminated by automation and AI. I am saying that this is not the norm, but the exception. Jobs are typically enhanced, not replaced.

I wrote before that AI is not a physical threat, largely because AI is not Artificial Consciousness. The same logic holds here. The creative leaps, intentionality, connection-making, and ambition that are the true engines of innovation in most companies simply is not being replaced by AI any time soon.

AI and automation make it so that every employee has a better chance to contribute significantly.

I leave you with two more proofs, and then a warning.

If you think that AI is a future threat to unemployment, I would not only emphasize that it is already widely-deployed now, but AI is already widely deployed in many cases for absolutely free. Google Maps, translation services, and soon voice-to-voice real time translation are free. Image recognition is used basically for free all the time everywhere. As is voice to text and text to voice in many automated phone systems.

If you though AI would compete with humans for jobs, how can they already be competing for something that is FREE?

The answer is that it’s not a competition.

The AI (and other automation) adds value to most workers.

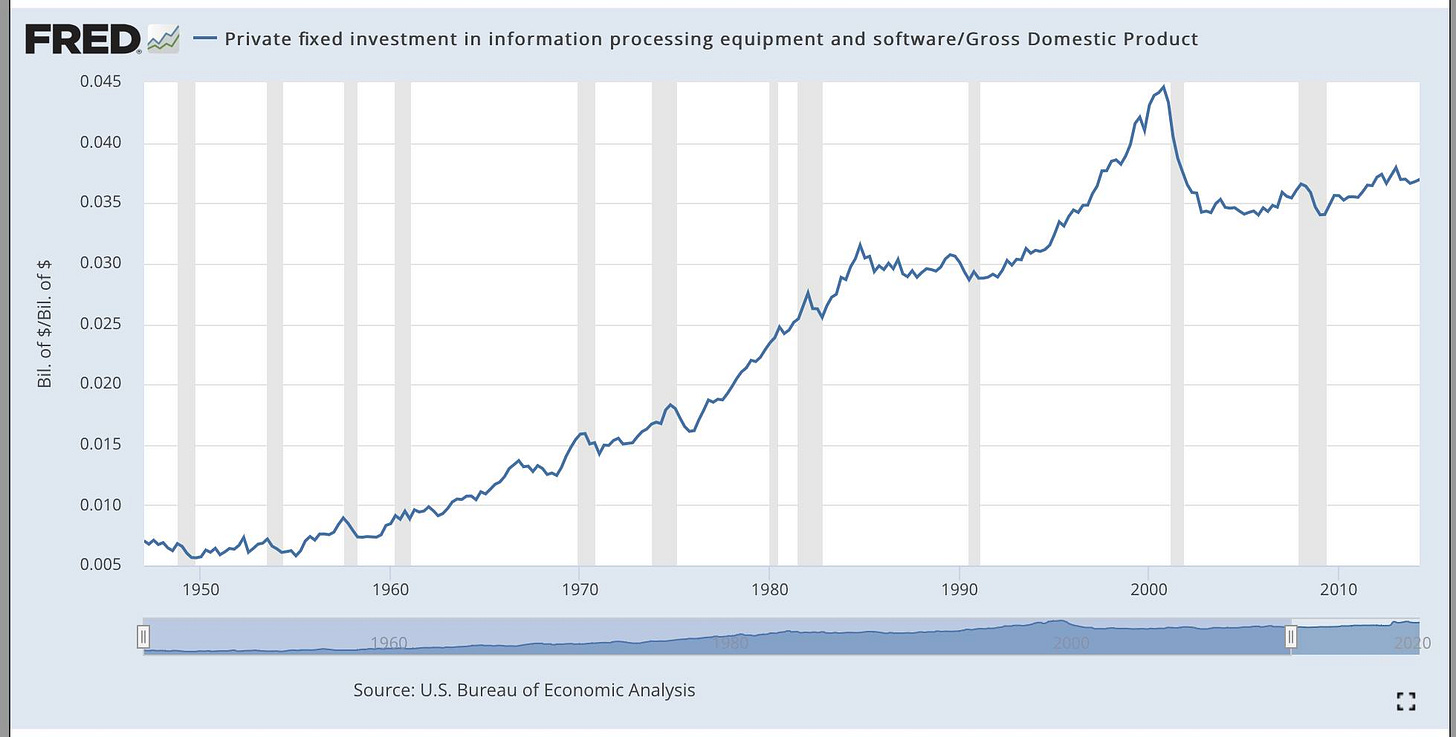

The last proof is that expenditures on computers and software (which would include all AI expenditures and most advanced automation) has not increased over the last two decades as a proportion of all company spending. If AI and automation were indeed a pathway to eliminating labor costs, then a huge proportion of the money would have been shifted from human labor to computers and software. We simply have not seen this, as the graph below shows clearly. The proportion of private (company) spending on computers and software has been basically flat at around 3.5-3.7% of all spending for almost 20 years:

And now for the warning: The people pushing for Universal Basic Income because of the impending automation-AI-unemployment cliff have been proven wrong over and over again. I believe that this article further drives home this point. These people are pushing a solution to a problem that simply does not exist. One may argue that one day it may exist, but it definitely does not currently exist at all.

And so one must conclude that they are just wrong in their worries, or they are attempting to deceive. There is vastly increased political power granted to governments if Universal Basic Income is passed. Huge swaths of the population would become deeply more dependent on the government. Worse, access to UBI would become the strongest non-violent lever of control over any type of dissent from the government ever. Criticize the government and they may make the Income not quite so Universal to you.

This is not a political blog, and I have no intention of making partisan political statements. I am not taking a left/right side. I am simply stating that there is currently no automation-related reason to do UBI, and it may be a bad idea for global human freedom.

Ironically, UBI might be a de-humanizing Societal Technology, while AI and automation might help make us capable of being our most powerful, truest selves.

Not sure I agree that the last graph supports the point you think it’s making.

From an individual firms perspective, wouldnt spending on (externally developed) AI appear as service procured in these accounts?

In which case this type of firm might indeed not require more (in fact less possibly, if cost saving) IT-outlay, but some big providers would have more of it…on aggregate a type of pattern that could look exactly like what we see in the graph?