The Simulation In Your Head

Tended properly, it can give you superpowers.

Animated tractography of a human brain By Alfred Anwander1 via Wikimedia Commons

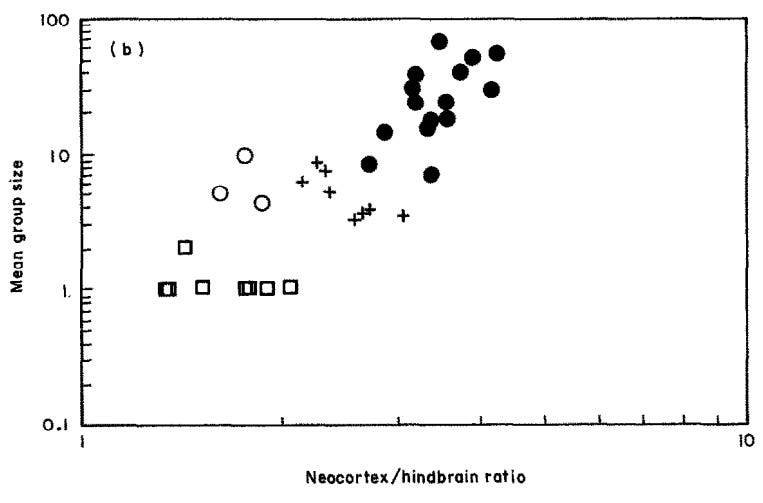

In 1992, Robin Dunbar, an anthropologist at Oxford, published the paper “Neocortex size as a constraint on group size in primates.” In it, he noted that the volume of the neocortex in primates is strongly correlated with the maximum size of social groups in that species. The bigger a species’ neocortex is, the larger that species’ “tribes” are.

In the graph above, the species’ neocortex volume is compared to its hindbrain volume. This is a useful way to look at things because it proportionally adjusts the neocortex volume in a way that accounts for changes in animal size. The hindbrain functionality is similar between species and thus its size is a base measurement that adjusts with the size of the animal. But these different primates show drastic differences in their neocortex size, and that is what appears to enable large functional societal groups.

“From the animal’s point of view, the problem is essentially an information processing one: the more information that an animal needs to be able to store and manipulate about its social or ecological environment, the larger the computer it needs” writes Dunbar in his 1992 paper. Dunbar’s data strongly bolstered the Social Intellect theory, which states that the amount of neocortical matter that a brain has limits the number of strong social interactions that it can keep track of.

What many people overlook, however, is that the calculations needed for social cohesiveness need to be incredibly fast.

So of course one of the first things that was done was to extrapolate out group sizes using human neocortex mass and mass ratios in our brains. And the number that Dunbar reached here is around 148 human tribe members. According to this relation, Dunbar hypothesized that the maximum number of strong friend and family relationships a human could simultaneously have is around 150.

Dunbar studied data on Facebook and discovered that the median number of close friends humans have is indeed very close to 150.2 And according to Dunbar, he has unearthed a wide range of indicators that human social group size is around 150.3 Of course, there are counter-examples and alternative statistical interpretations refuting the exact number of Dunbar’s relationship, but as of now it appears that there is some computational relationship between neocortex size and the number of close social interactions.

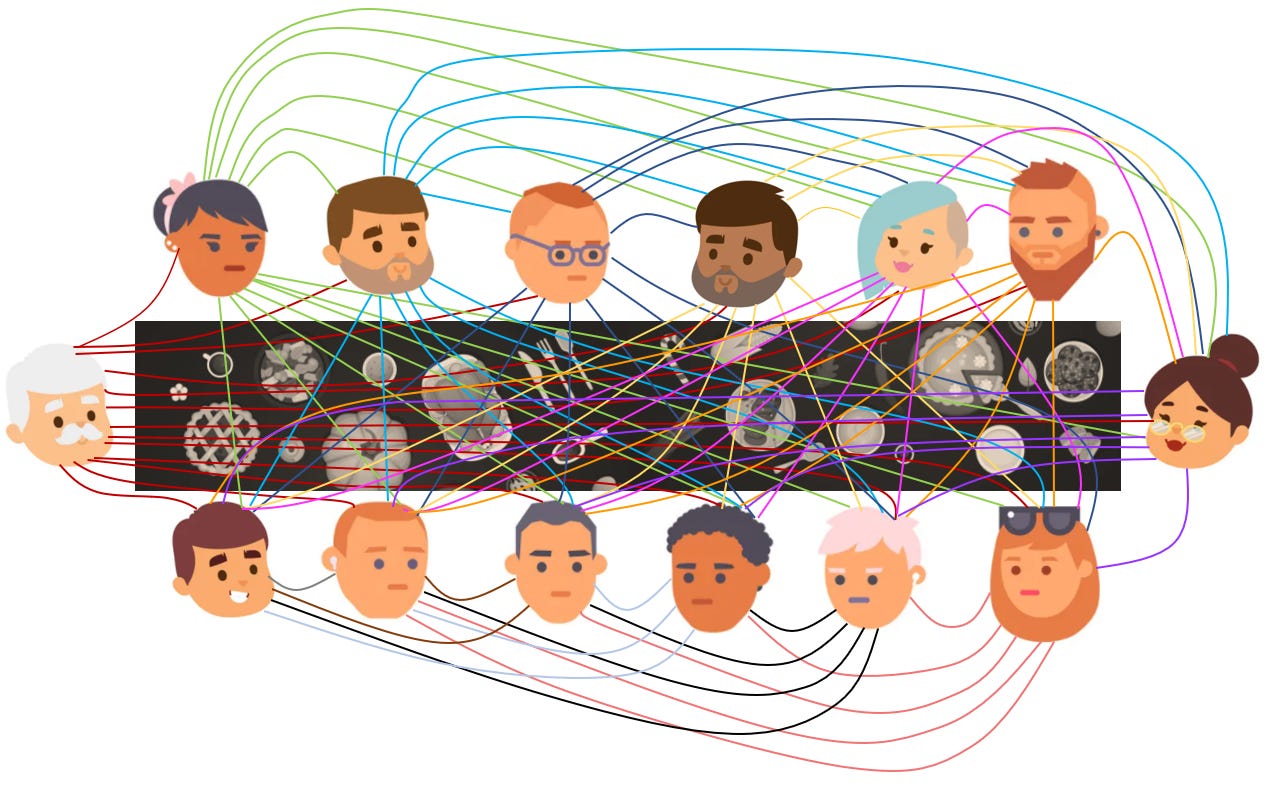

What many people overlook, however, is that the calculations needed for social cohesiveness need to be incredibly fast. Think about a Thanksgiving table conversation (or any large family gathering). If cousin Andy makes a comment about kids born outside of marriage, everyone at the table has to instantly know how to respond in many subtle ways. Assurances of inclusion must be hinted to at Tom, who grew up with a single mom. Bethany had a child in high school but quietly put him up for adoption — you know that, and so does your mom, but you can’t put an arm around Bethany because then Sandra would find out, and Bethany doesn’t want Sandra to know because she thinks Sandra would judge her; but you secretly know that Sandra didn’t know her birth mom and resents her mother for that, so if Sandra found out she might say something hurtful to Bethany.

And you don’t have 5 minutes to sit down and trace out all these very complex relational facts. You have to “calculate” how to act in less than 1 second. This is even more amazing because you don’t just calculate how these people know each other or what they value. You have to actively simulate in your head what would go on in their heads if different things were said or done by you. Further, you have to quickly scroll through multiple different possible responses, with all the cascading possibilities of reactions, in real time. In the “Thanksgivingogram” above, there are 13 other people whose thinking you have to simulate, and also 13+12+11+…+3+2+1 = 91 ways that people see each other, plus your own goals for the conversation. And yet, most people know what to say (or not to say) in conversations in real time, in perhaps a few hundred milliseconds.

This is absolutely fantastical.

The important take-away for this discussion is that it appears that our brains have specialized hardware for very quickly calculating multiple sets of densely correlated abstractions.4 This social hardware works so well that it usually performs these calculations effortlessly and subconsciously. The answer is presented to our consciousness as if by magic, tagged with an emotion that helps us decide what to say in the moment.

How is this possible? We don’t know, but we think it has something to do with the extreme interconnectedness of the neocortex. Below is a representation from the EPFL Blue Brain portal of a mouse brain5 showing only 3% of the actual connections in this region. Note how the density of connections is drastically increased within the neocortex, which is the space between the yellow dashed lines (added by this author).

And if that blows your mind, hold on to your cortex.

It appears that our neocortex matter is strongly interconnected, but also modular. Jeff Hawkins in his book A Thousand Brains: A New Theory of Intelligence6 describes the neocortex as being largely comprised of 150,000 cortical columns of similar design, each strongly interconnected by dedicated paths to many other cortical columns. This modularity is probably largely responsible for the ability of humans to abstract out concepts from messy data. It also provides insight into how humans can then mentally manipulate the relationships and interactions of abstract concepts, playing them against each other in mental space. Stanislan Dehaene and others have postulated that neuronal circuitry is repurposed in order to perform novel cultural purposes such as reading.7 Michael Anderson has similarly argued that on evolutionary and lifetime scales, neuronal circuitry can be co-opted to perform new sets of tasks.8

…this means that we can use our insanely strong social calculator to do other calculations at similar speed.

So if we do indeed have these generalized but powerful dedicated abstraction modules in our heads that can be repurposed, then this means that we can use our insanely strong social calculator to do other calculations at similar speed.

By feeding a lot of accurate data about how the world works into our minds, we build more and more accurate representations of real world things into our minds. Then, when we need to know how an action or invention or process will play out in the real world, we can instantly know how it will play out. This, without ever actually touching or building anything.

I will switch into first person mode to provide a personal example. All my life I have been insanely curious. I’m not the brightest guy around; but as best I can tell, I am one of the most curious. So I have always been jamming my brain with as much data as possible in terms of geology, astrophysics, economics, material science, particle physics, philosophy, electromagnetics, microbiology, fluid mechanics, dynamics, and the like. Happily, this turned out to serve me well when I worked as a research engineer. I would be presented with a complex set of requirements. For instance, a person may say that they need to measure the the temperature of a rotating jet turbine blade in real time for 1,000 hours at 1,000°C. Instantly, I was able to evaluate what temperature and g-load would do to the materials involved. I also could see what types of circuits and bonding arrangements could be used to perform sensing of temperature, and how such a signal could be transmitted from the blade. In around one second, I had instantly rejected perhaps hundreds of design paths, narrowing them down to just one or two approaches that had the best chance of working.

This is largely what “expertise” is.

My knowledge bases of materials science, electrical engineering, electromagnetics, and high-nickel-steel tensile properties all related to each other within the boundary conditions of the jet engine environment, because each of those had been abstracted into highly connected models of reality in my head. I had used my social calculation hardware in a way that had replaced Uncle Jim with ceramic adhesion qualities and Grandma Mae with metal oxidation rates. Also, I understood the connections between them: that over temperature the ceramic would expand less than the steel, while the ceramic also might provide some thermal protection to the steel but be fragile under heavy vibration.

One important takeaway is that you likely already do this. If you are an expert in Minecraft, and I ask you how to create an automated mob-spawning loot collector,9 you will instantly reject hundreds of bad designs. You will have used your social calculator hardware that had been repurposed to understand how the game world of Minecraft works in order to get to a working machine design very quickly.

The best part is that tending your social calculator hardware to give yourself new superpowers is simple and fun: be very curious and do deep dives on reliable information.

The same is true if I asked a world-class welder how to combine titanium and iridium in a vacuum for cryogenic use in a high-radiation environment. Even though she may have never thought about doing such a bizarre and unique thing, she brings to bear instantly a lifetime of very accurate welding models that inform her of a solid path forward almost subconsciously. Then she would take those one or two best paths and consciously research them in a more painstaking manner.

The best part is that tending your social calculator hardware to give yourself new superpowers is simple and fun: be very curious and do deep dives on reliable information.

That “reliable information” part is not easy at first. But as your web of knowledge increases, it becomes easier and easier to spot bad information and reject it. Things that don’t fit your existing knowledge base raise alarm bells. That said, open-mindedness is also important, or new information will never find a home in your neocortex abstraction modules. Also, do deep dives on areas outside your current area of expertise. The world is filled with wonders everywhere.

Having that ability to weed out all the bad ideas during a creative process instantly is indeed a superpower. It makes your creative processes much faster and more effective. You don’t waste nearly as much time going down blind alleys to dead ends. New possibilities will leap unbidden from your mind.

The broader, deeper, and more accurate the Simulation In Your Mind is, the more your superpowers will grow. Just keep in mind that they come with great responsibility.

“The evidence that personal social networks and natural communities approximate 150 in size, characterised by a very distinctive layered structure, has grown considerably in the past decade. We see it in telephone calling networks, Facebook groups, Christmas card lists, military fighting units and online gaming environments. The number holds for church congregations, Anglo-Saxon villages as listed in the Domesday Book and Bronze Age communities associated with stone circles.”

- Dunbar, May 2021, https://theconversation.com/dunbars-number-why-my-theory-that-humans-can-only-maintain-150-friendships-has-withstood-30-years-of-scrutiny-160676

I don’t mean people are abstractions. What I mean is that our understanding of their personality and thinking that we hold in our brain is, necessarily, an abstraction — a tagged representation of reality of somewhat lower resolution than reality.

Dehaene, S. (2009). Reading in the brain: The science and evolution of a human invention. New York, NY: Penguin Group

In Minecraft, one way to collect loot (goods and items) is to kill enemies that spawn in the game. People have learned how to trigger enemies to spawn at “unnaturally” high rates using certain subtle ways to trick the game engine. Then when the mobs spawn those enemies are often automatically killed, and their loot is funneled to some collection bin where the player collects it. Yes, this is a thing. Click the picture to see the video after you finish these last few paragraphs of the article.

I always enjoy reading your articles Joshua; you never disappoint.

Thank you for sharing your brilliant insights so freely.

Kind regards,

Terry Terezakis